“Although I may not have been able to articulate it, I already felt these alien streets would be a trial, filled with unfamiliar faces and unfamiliar tongues. How could I make a friend when I didn’t even speak English? How could I understand a teacher or classmate? And how could I rely on my perplexed, frightened parents to help me cope?”

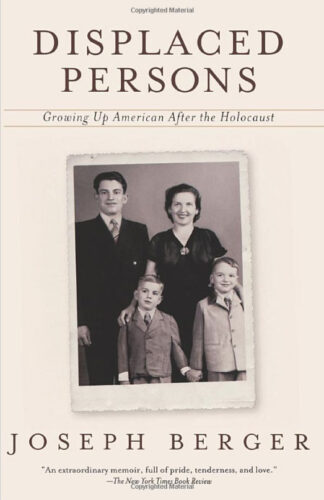

So begins veteran Joseph Berger’s beguiling account of how one family of Polish Jews — with one son born at the close of World War II and the other in a “displaced persons” camp outside Berlin — managed to make a life for themselves in an utterly foreign landscape. Displaced Persons speaks directly to a little-known slice of Holocaust history, illuminating as never before the experience of 140,000 refugees who came to the United States between 1947 and 1953.

The world of Manhattan’s Upper West Side, in the shadow of Hitler’s atrocities, has been the subject of some of Isaac Bashevis Singer’s best fiction. But through the eyes of a bright and perceptive boy we come to understand the reality on a more visceral level. Like many immigrants and children of immigrants, Berger lives in two worlds at the same time. On the one hand, there is this thrillingly rich American turf to explore as a child, and he does a brilliant job of bringing that adventure to life. On the other hand, he never lets us forget what it’s like to feel intractably rooted in another, incompatible world of refugee parents who cannot speak English, a world of people dazed from unimaginable loss, and whose loneliness is unrelenting.

Berger pays eloquent homage to his parents’ extraordinary courage, luck, and hard work. For as he says, “If we, the sons and daughters of those who survived, will not remember their vanished world, who will?” But Displaced Persons also testifies to the frustratingly hardy state of being a refugee — no matter where one’s initial port of call happens to be and no matter how much success has been achieved in the adopted country. By writing so sweetly and honestly about this “indelible way of seeing the world,” Berger has shed a warm light on a perennial, universal condition.